The days of the generalist are gone. Long live the specialist!

Is it better to be a generalist or a specialist? Gaétan de Rassenfosse, who holds the Chair of Innovation and IP Policy at EPFL, set about answering this question by digging through data on more than 30,000 biomedical researchers. In terms of career impact, the answer couldn’t be clearer: specialization confers a significant, long-lasting advantage. This finding, which could be extrapolated to other disciplines, is outlined in a paper appearing in BMC Biology. It confirms that the days of the Renaissance generalist are gone, and that we now live in the era of the specialist.

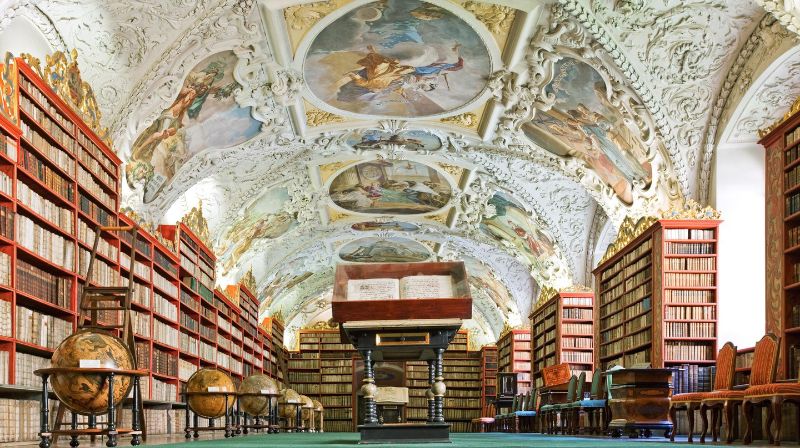

“The idea that we should aspire to be consummate generalists, like Leonardo de Vinci, belongs to a bygone age,” says de Rassenfosse, an Associate Professor at EPFL’s College of Management of Technology (CDM). “These days, you have to specialize.” One of the main reasons for this shift is that, even with the benefit of modern technology, the entirety of human knowledge is too much for a single person to accumulate in a lifetime. Nowadays, mastering a small corner of a field within a given discipline – a niche within a niche – makes more sense. But does this approach pay off for scientists looking to make a name for themselves in the narrow confines of academia?

An invisible college

For their study, de Rassenfosse and his colleagues employed methods from the social sciences to measure the extent to which specialization affects a researcher’s career prospects. Their study couldn’t have come at a more opportune time: a recent report by the Swiss Science Council (SSC) found that just 1% of a cohort of postdoctoral researchers at Swiss universities obtained a professorship in Switzerland within four years of starting their postdocs.

The paper’s three authors analyzed data on 30,000 researchers who had published 100 articles or more over 30 years. Their study focused on biomedical research because the data were readily available. “But we might expect similar results for other disciplines,” says de Rassenfosse. In broad terms, the authors looked at the number of citations their articles received and measured changes in the researchers’ popularity and visibility over the course of their careers.

Their first finding was that specialization raises visibility: articles by specialists receive 25% more citations than papers published by generalists. They found that specialization is even more rewarding earlier in a researcher’s career, increasing citations by 75%. And although this benefit is less pronounced later in a researcher’s career, specialization still has a positive effect. The authors also observed that the rewards are higher for researchers who publish fewer papers. “Researchers are part of what we call an ‘invisible college’ – a community of like-minded people that operates somewhat like a social network,” explains de Rassenfosse. “When you specialize, you raise your profile within your community.”

Specializing has its downsides

Specialization isn’t just the preserve of academia. Mastering a niche is becoming increasingly important in a range of fields, from medicine, law, and economics to sports, computer science, jewelry-making, and more. “As a result, it’s getting harder for experts to communicate with one another,” adds de Rassenfosse. “That’s why interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches have never been so vital – and, often, so challenging.”

Specializing also has its downsides: researchers who focus on too narrow a niche can end up becoming overspecialized, chasing dead-end lines of inquiry or mastering technology that later becomes obsolete. Again, this risk isn’t exclusive to academia. What’s more, many early-career researchers find it hard to pursue their initial specialization. “When you’ve completed your PhD at a cutting-edge laboratory, finding another lab to take your research further can be tough,” says de Rassenfosse. “And there’s the fact that researchers often struggle to distance themselves from their thesis topic. That can be helpful, but it can also hold people back. Sometimes, you have to accept that you’ve bet on the wrong horse and change course.”